Commencement Address, College of Education, University of Missouri, St. Louis

May 14, 2017

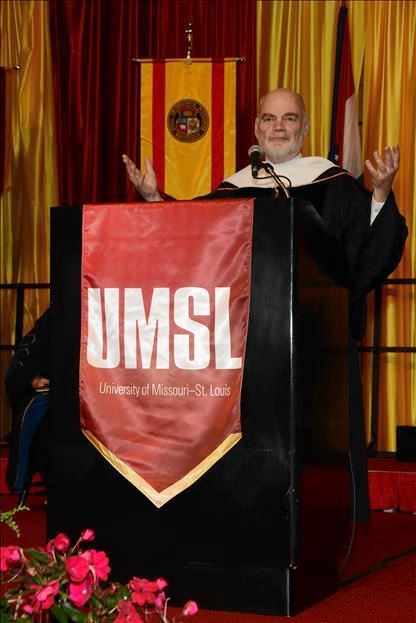

Tom speaking at the UM-St. Louis College of Education graduation ceremony.

Thank you, Chancellor. I appreciate the honor of being asked to speak at graduation and I appreciate the honor of receiving an honorary doctorate.

Happy Mother’s Day!

Even more, congratulations to all of our graduates.

You know, it’s easy to be concerned about the world. If you read the newspaper, watch the television, or listen to the radio, it seems that all you hear is bad news. There is a lot of bad news! So, it’s easy to be discouraged.

But then I see this sea of UMSL graduates ahead of me and I become encouraged.

I know that they are they are going to make a difference in the world, use the training they have received here at the University of Missouri-St. Louis, and make a positive difference for kids. And each of those changes will ripple into the world. In advance, thank you.

Let me begin my talk with an historical survey.

Everyone, think back to the graduations you’ve attended – grade school, high school, college. Now, raise your hand if you’ve already been to at least three graduations. How about six? Anyone been to more than a half-dozen?

OK, now raise your hand if you remember anything that any of the graduate speakers ever said.

With that wave of enthusiasm, I’m going to break the mold.

I am going to give you three lessons that will apply to whatever you are doing, and I am confident that you will remember them. You may or may not remember the speaker, and that’s not important, but I am sure that you will remember these lessons.

First, you can be a Mrs. Mayfield.

I realize that you don’t know who Mrs. Mayfield was. Well, she was my first-grade teacher many years ago, at Monroe School, near Broadway and Chippewa in south St. Louis.

I don’t know if Mrs. Mayfield was pedagogically talented and creative. I don’t know if she was knowledgeable about her subject matter, and I don’t know if she worked well with the other teachers and the principal.

I do know that Mrs. Mayfield changed my life.

I was a disheveled little boy, couldn’t sit still, not much of an attention span, not a good listener, and talked too much. But Mrs. Mayfield believed in me. She recognized my challenges and worked with me to improve, but she also saw my strengths and she helped me develop them. She saw my potential. She believed in me, she knew me, and she cared.

Too often we only focus on what kids don’t do well. Yes, students do need to be able to read, write, and calculate, and she should focus on these areas, but we cannot stop there. We must also see them through their strengths and help them develop their talents and pursue their potential.

My second lesson is to make new mistakes. I understand that mistakes are bad and we don’t like to be wrong. But too often we find something that works and we simply continue to do it. We have our formula, but the world is changing around us and we aren’t learning.

We learn from our failures, not from our successes.

Making old mistakes, making the same mistake over and over, isn’t good, but it’s also not good to make no mistakes. Instead, we need to get out of our comfort zones and try new things, we need to learn from our new mistakes, and we should encourage our students to do the same thing.

A term I’ve coined that captures this is “good failures.” Failures aren’t good but a good failure is one from which you learn. Thinking about good failures encourages us to take risks, try new things, and learn from our experiences.

The third lesson comes from a newspaper column.

Every Sunday I enjoy reading the NY Times, and a favorite piece is the column, “Corner Office” by Adam Bryant. In it, he interviews CEOs, asking about how they were raised, how they got into their business, how they define leadership, how they hire, and so on. The column is always good but one that really struck me appeared in April 2016.

The person interviewed was Walt Bettinger, the CEO of Charles Schwab investment company. Bettinger talked about how he prided himself on having a straight-A average all through college. It was his last class, Bettinger said, one on business strategies, and he was ready for the final. He had studied all week, memorizing formulas, and he had stayed up late the night before, cramming. He was ready!

The professor walked in, Bettinger relates, and gave everyone a blank sheet of paper, nothing on the front or back. There’s only one question on this exam, the professor said, write down the name of the person who cleans this building.

Bettinger said that he had no idea who it was. He handed in the paper and received an F on the test and a B in the class, but Bettinger said it was the best lesson he ever learned. We need to take the time to know everyone, regardless of the job they have or where they are in the hierarchy. We need to related to them as human beings.

Last week I was in New City School, and I saw Johnny Burton, the wonderful guy who cleans our building and keeps us safe, and I gave him a big hug. And I saw Joyce Lanos, the receptionist who answers the phones with a smile and gives New City its personality. I gave her a hug – and a bag of chocolate-chip cookies.

It’s too easy to overlook these folks and not give them the time and care that they need, and that’s not right. I call this lesson “who you are is more important than what you know.”

So, my three lessons are Be a Mrs. Mayfield, make new mistakes, and remember that who you are is more important than what you know.

Thank you for the opportunity to speak, and I look forward to learning about all of the exciting and wonderful things that our UMSL graduates will do!