Multiple Intelligences Newsletter, Vol 30, No 3

November 1, 2020

Hi Friends,

How are things going for you? I hope that you’re safe and not suffering from too much Zoom fatigue. I’ve talked to many, many teachers and principals, and it seems that everyone is working harder and longer in these COVID days than before. Of course, these difficulties are exacerbated when we don’t get to be with our students in person and experience their smiles and joyful learning. It seems that in many schools, students are beginning to return to the buildings, so let’s cross our fingers and hope that everyone stays healthy and safe.

In July, this newsletter featured an article by Howard Gardner, “A Resurgence of Interest in the Existential Intelligence: Why Now?” In it, Gardner defined a possible Existential Intelligence (no, he’s not anointed it as one of the MI) as “the cognitive capacity to raise and ponder ‘big questions’—queries about love, about evil, about life and death — indeed, about the nature and quality of existence.” He wrote about the stress and anxiety that COVID-19 is causing, coupled with – exacerbated by – the intense political debates here in the U.S. He said, “The combination of threats, on the one hand, and time to think, on the other, has also affected the timing of my thinking and what I think and read about.” Gardner is correct: many of us are pondering BIG, existential, questions (I know that I am). In this issue, one of our readers, Bahram Ghaseminejad, the head of Kourosh Elementary School in Karaj, Iran, offers a very eloquent response to Gardner. I am sure you will find it interesting.

I often see articles which refer to MI – using a non-scholastic intelligence to solve a problem or create a product – although the term “multiple intelligences” isn’t used. Here’s one such example from Education Dive, “Three Steps to Integrating Art Into Other Classes,” by Lauren Barack.

The last issue featured an article, “Growing the Personal Intelligences: A Study In Deep Learning,” by our New Zealand friend, Alan Cooper. In fact, the credit for the article should have been shared with Mary Stubbings. She is an Accredited Facilitator at the Poutama Pounamu (Excellence, Equity and Belonging) Te Kura Toi Tangata, Faculty of Education, University of Waikato. I am sorry to have omitted her.

And perhaps to lighten your mood, below you’ll see a depiction of me drawn by a New City School kindergarten student. Best – or maybe it’s worst! – it’s pretty accurate! Thanks for your interest and stay safe. I’d be delighted to hear from you.

TOM

Thomas R. Hoerr, PhD

Emeritus Head of the New City School

Scholar In Residence at UM-St. Louis

Exploring the Existence of Existential Intelligence

By Bahram Ghaseminejad, Head of Kourosh Elementary School, Karaj, Iran

I have never heard from anyone

Why I was brought here, and why taken away.

Omar Khayyam

Nowadays, all around the world everyone is talking about the COVID-19 pandemic, and how it has affected our lives in numerous ways. Maybe, regardless of the dear lives this deadly virus has taken, it’s somehow also a blessing in disguise, by letting us slow down a bit and allowing us some time to ponder “big questions” about the nature of our existence; hence, the rise in the number of inquiries about the possibility of the existence of “existential intelligence,” which Dr. Gardner abbreviates as “Ex I” and will be abbreviated here as such.

In his article in the July issue of MI Newsletter, Dr. Gardner made an eye-opening analogy to Albert Camus’ novel The Plague where the setting is somewhat similar to ours today. Between the lines, the novel addresses the human predicament and a desperate search for meaning under the dire circumstances. It seems — by force or by choice — every now and then we need to pause and dig into essential “existential questions” that are deeply rooted in every fiber of our existence; questions about good and evil, life and death, and the meaning and purpose of life. In the search for meaning, apparently every human being needs to know — or at least ponder some big questions — as in Omar Kayyam’s words, “why I was brought here, and why taken away.”

From the East to the West, from the past to the present, great artists, poets, and philosophers, even simple men and women, have contemplated fundamental questions. John Keats, the great English poet, addresses the concept of eternity in “truth and beauty” as a big question in his poem “Ode on a Grecian Urn” as such: “Beauty is truth, truth beauty, that is all / Ye know on earth, and all ye need to know.” Is that really all we “need to know”? Well, the point is the poet suggests that it is a major question to consider. It is a philosophical statement about permanence and the ultimate beauty of art, or whatever stands the test of time, which needs to be asked.

Poets, novelists, playwrights, artists, psychologists, and philosophers tend to maintain their childhood curiosity to ask quintessential questions. Those rudimentary questions are a proof of man’s quest for making sense of his life on earth, as addressed by Viktor Frankl in his book Man’s Search for Meaning. Frankl believes “those who have a ‘why’ to live, can bear with almost any ‘how.’” But why is “the why to live” so significant?

Maybe it’s because it gives one the sense of meaning and fulfillment; it answers the big questions by answering why we do what we do.

Throughout history, humans have been preoccupied with basic philosophical questions in different forms, which itself suggests the significance of multiple intelligences, since each person expresses his or her preoccupation in a different way. Some write, some draw, some compose music or make movies; nevertheless, the preoccupation with big questions abounds in different forms in all cultures. So it seems there could be the possibility of another intelligence called Ex I.

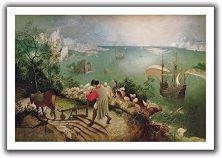

All of us have heard the story of the famous myth of Daedalus and Icarus. Using his spatial intelligence, Pieter Brueghel painted the fall of Icarus into the sea in one corner of the picture, while the rest has nothing to do with it, in order to show how life goes on after our death, as if the passing away of Icarus — or any other one of us — is nothing of significance to the world. We know it is a myth, but there’s an element of truth about existence in it. Why should humankind be concerned with life and death? That is definitely a big question which has been raised time and time again.

About 400 years later, W.H. Auden sees the painting and addresses the same question, using his linguistic intelligence. Maybe Brueghel and Auden also tapped into their Ex I to express their preoccupation with this question.

After seeing Brueghel’s painting, Auden wrote a poem titled “Musée des Beaux Arts.” Pondering the question of existence and referring to Brueghel’s painting, Auden ends his poem like this:

The Fall of Icarus, Pieter Brueghel

In Brueghel’s Icarus, for instance: how everything turns away

Quite leisurely from the disaster; the ploughman may

Have heard the splash, the forsaken cry,

But for him it was not an important failure; the sun shone

As it had to on the white legs disappearing into the green

Water; and the expensive delicate ship that must have seen

Something amazing, a boy falling out of the sky,

Had somewhere to get to and sailed calmly on.

“Musée des Beaux Arts,” W.H. Auden

The same concern can be traced in the movies by great film directors in search of meaning like Steven Spielberg, Andrei Tarkovsky, Akira Kurosawa, Stanley Kubrick to name just a few. The Legend of 1900 by Giuseppe Tornatore is one such movie where big questions like infinity and the endlessness of creativity are raised. The protagonist who is a pianist and is called 1900 in the movie says:

“Take piano: keys begin, keys end. You know there are 88 of them. Nobody can tell you any different. They are not infinite. You’re infinite… And on those keys, the music that you can make… is infinite. I like that. That I can live by.”

The Legend of 1900, Giuseppe Tornatore

Human beings have constantly been possessed with the concept of time and shortness of life; this is revealed in numerous works of art in different cultures. As an example, the English poet Andrew Marvell reveals his preoccupation, urging us to practice carpe diem:

But at my back I always hear

Time’s wingèd chariot hurrying near;

And yonder all before us lie

Deserts of vast eternity.

“To His Coy Mistress,” Andrew Marvell

Life is short, and the race with time has always been breathtaking. This appears in different forms of art. A musical expression is created by Pink Floyd, accompanied with the following lyrics:

And you run and you run to catch up with the sun, but it’s sinking,

Racing around to come up behind you again.

The sun is the same in a relative way, but you’re older,

Shorter of breath and one day closer to death.

“Time,” from The Dark Side of the Moon, Pink Floyd

Great thinkers and poets have frequently raised fundamental questions in different ways. With a touch on empathy and the meaning of life, Emily Dickinson writes a wonderful poem to attract the attention of her readers to make them think deeply. Life is not just about getting and spending; it’s about thinking and making sense of why we are here on earth for a while. Here’s how Emily Dickinson contemplates the purpose of life:

If I can stop one heart from breaking,

I shall not live in vain;

If I can ease one life the aching,

Or cool one pain,

Or help one fainting robin

Unto his nest again,

I shall not live in vain.

“If I Can Stop One Heart from Breaking,” Emily Dickinson

If we don’t want to live in vain, we ought to ask big questions. It seems to be a natural tendency; maybe an intelligence needing to be developed. We should take our time once in a while to dig into the depth of our being. The COVID-19 pandemic is one such time when we are given some time to think, albeit by force; or maybe like Thoreau we can choose to go to the woods and contemplate.

I went to the woods because I wished to live deliberately, to front only the essential facts of life, and see if I could not learn what it had to teach, and not, when I came to die, discover that I had not lived.

Henry David Thoreau

Furthermore, the Persian poet Rumi, who wishes to make his readers think deeply about their existence, points out:

You’re not a drop in the ocean;

You’re the entire ocean in a drop.

Rumi

The case for existential intelligence appears to be strong. Maybe we are born with an innate capacity to ponder big questions. Considering numerous examples in art and mythology throughout history, Ex I could be deeply rooted in the human brain. Great thinkers, writers, and artists seem to excel at raising rudimentary questions, and they trigger our sense of curiosity about our existence. Questions as essential as why I was brought here and why taken away. Am I a drop in the ocean, or the entire ocean in a drop? Where does the urge to ask big questions come from? That is the question.

ASCD

This Professional Interest Community (PIC) is sponsored by ASCD as part of their effort to improve the quality of education for all children.

ASCD PICs are member-initiated groups designed to unite people around a common area of interest in the field of education. PICs allow participants to exchange ideas, share information, identify and solve problems, grow professionally, and establish collegial relationships.

You can learn about ASCD’s networks, publications, conferences, workshops, and the dialogues sponsored by ASCD at www.ascd.org. You can also register for the free, daily ASCD SmartBrief.

I’d like to hear from you! Please send me an email at trhoerr@newcityschool.org