Multiple Intelligences Newsletter, Vol 34, No 1

August 10, 2024

Hello to MI Friends,

As we embark on another school year, I offer some sound advice to everyone who deals with children. Regardless of your role – educator, parent, family member, neighbor, or friend – please make a point of asking children, “How do you have fun?” and “What are your talents?” It is important to recognize and validate children’s strengths.

Sadly, that’s not the usual approach to asking children about their progress. Only asking “How’s it going in school?” addresses the linguistic and logical-mathematical intelligences and reinforces education’s traditionally narrow route to success. Put another way, too often we ignore children’s multiple intelligences. We overlook their strengths in music, art, nature, and athletics; we discount their skills in managing their emotions and leading others. Having an MI perspective means recognizing the range of talents that we all possess. It means acknowledging children’s passions and appreciating what they can do.

For educators, a recognition of MI means enabling students to learn through their stronger intelligences. It doesn’t mean discounting the 3R’s; it does mean that students can learn and express their understanding in a variety of ways. For relatives and friends, a recognition of MI means asking children what they like to do in their free time; it means inquiring about their hobbies.

Using an MI approach applies to us, too. We should reflect on how we spend our free time. What do we do for fun and which intelligences does this reflect? How different would we be today if we had been able to use those intelligences in learning while in school?

Recognizing the multiple intelligences that we all possess means identifying and appreciating our strengths. Wouldn’t it be a better world if we all did that?

TOM

Thomas R. Hoerr, PhD

Facilitator of the MI Network

The Basis of MI

For the past decade, after retiring from the New City School, I have been teaching in the College of Education at the University of Missouri-St. Louis (UMSL). I work in the educational leadership preparation program, and it’s really enjoyable. My students are talented and I learn a lot from them. Recently, one of my students, knowing that I led an MI school, asked about the “empirical research basis of MI.” My response might be useful, so I share it here.

I wrote to her: “Your MI question is a good one, and it raises into question the definition of ’empirical.’ Howard began by defining intelligence as ‘the ability to solve a problem or create a product that is valued in society.’ He then arrived at MI at looking empirically, though not experimentally, at how people solve problems. He identified seven different approaches, different intelligences, from looking at problem-solving very pragmatically.

“To me, an easy question is whether a wonderful work of art or a fine musical rendition reflects intelligence, or what about a leader who can create a team out of chaos? The nay-sayers would admire those achievements but refer to them as talents. As Howard has said, it’s fine if they’re talents but then so is proclivity in writing and math. Or they’re all intelligences. While the economic world has a hierarchy of intelligence (linguistically skilled lawyers typically earn more than musically skilled performers), from an intelligence perspective, they’re all equal, their value depending upon the context, i.e., the problem to be solved.

“I do not know of formal research studies on MI (although some exist; I never pursued them). In part, this is because unlike standardized tests which draw from the linguistic and logical-mathematical intelligences, an MI test would need to provide multiple pathways and then somehow measure their effectiveness. Creating such a tool would be cumbersome and expensive, and for what purpose? Why not just observe how people solve problems (which Howard did).

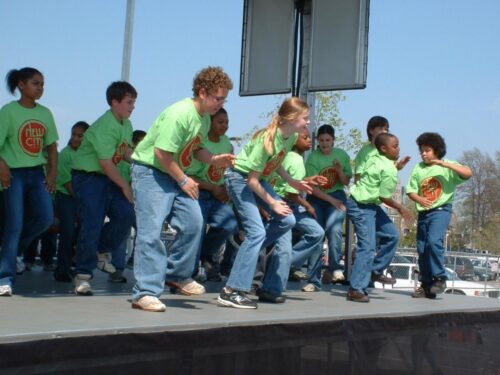

“Finally, from a personal perspective, I can speak empirically to the power of MI. I led the New City School for 34 years, from 1981-2015, and we were an MI school from 1988-2015. Thus, I saw first-hand how teachers used different intelligences in presenting content, how they gave kids different ways to solve problems by enabling them to use their strongest intelligences (and sometimes forcing kids out of their comfort zones by requiring them to use less strong intelligences). Assessment was traditional – we gave standardized tests in grades 1-6 and used percentages on progress reports – but we also used MI as part of our assessments, including a Portfolio Night. And following our belief that ‘who you are is more important than what you know,’ for all students age 3 through grade 6, our report card began by focusing on the personal intelligences.”

I hope you agree that my response puts “empirical” in the proper perspective. I’d be delighted to hear your thoughts!

This Professional Interest Community is sponsored by ASCD as part of their effort to improve the quality of education for all children.

You can learn about ASCD’s networks, publications, conferences, workshops, and the dialogues sponsored by ASCD at www.ascd.org. You can also register for the free ASCD SmartBrief.